Since the creation of the Pepperstone ATP Rankings in August 1973, 28 men's singles players have owned the No. 1 spot. From Ilie Nastase in the very first edition to Carlos Alcaraz today, these unique superstars from across the world are forever linked, part of the elite fraternity to reign over the men's game.

ATPTour.com is celebrating the coming 50th anniversary of the Pepperstone ATP Rankings with a five-part series looking at the legendary players, their epic battles, the inspiring comebacks, the jaw-dropping milestones and statistics and other narratives that showcase one of the most talked-about elements of our sport.

Leading tennis author and historian Richard Evans, who knows better than most all of the players to reach World No. 1, kicks us off with his personal reflections on the most notable among this elite group to have reached the pinnacle of tennis.

[ATP APP]

Photo by Steve Powell/Getty Images

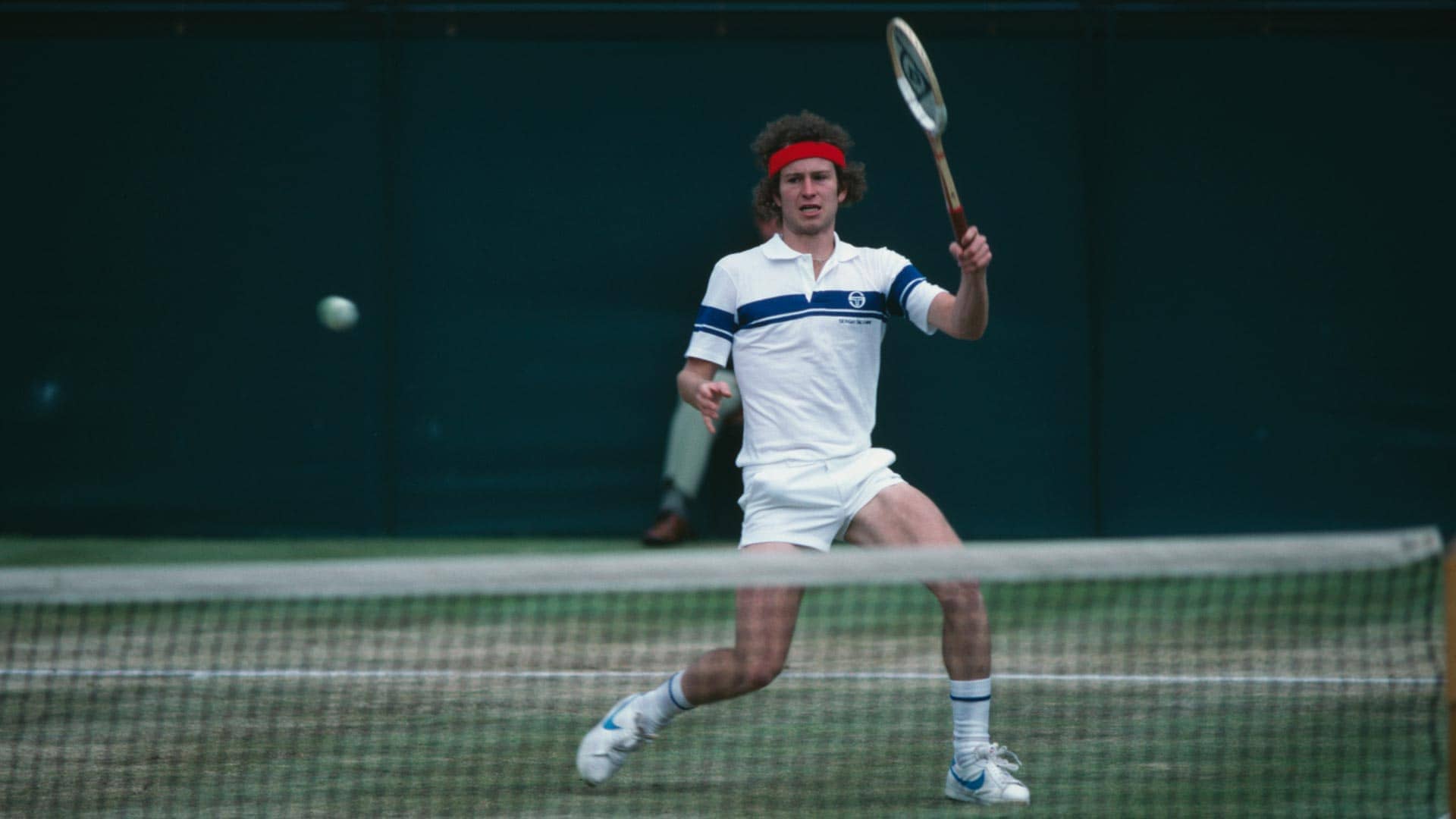

John McEnroe

Considering the level of natural skill with which he was blessed, it could be said that McEnroe’s total of seven Grand Slam singles titles and 77 overall makes him an underachiever. Lethal with feathery touch on the volley after swinging his left-handed serve way out wide to the ad court, McEnroe rose to World No. 1 at the age of 21 in 1981. In 1984, he put together the best season in ATP Tour history by winning percentage (96.5 per cent), soaring to an 82-3 record.

However, a combustible temperament bound up with an inability to accept umpiring decisions that he felt sure were incorrect (technology would have proved him right most of the time) benefited no one more than his opponents — Ivan Lendl, two sets and a break down in the 1984 Roland Garros final, being a prime example. McEnroe will admit to having nightmares about that loss today but there is one excuse few people know. Having flown to London that night, I met John at The Queen’s Club the next day and he invited me to touch his scarlet forehead. It was still hot. He had suffered sunstroke and took to wearing a headscarf afterwards.

For those trying analyse the McEnroe character, his headmaster at Trinity School in Manhattan told me something that will surprise many. I asked how “Johnny Mac” behaved in school matches. “Fine,” was the answer. “We didn’t have umpires. John gave any tight calls to his opponent. He never wanted something he had not earned.” The headmaster might have added that McEnroe could not tolerate being deprived of something he HAD earned.

Sensitive to the slightest sound and aware of every disruption, McEnroe’s nervous system was easily rattled. I was standing seven rows back on the packed Queen’s Club terrace one year and sneezed just as McEnroe was about to serve. I had been there one minute. He stopped, turned and said, “Oh thanks, Richard.” That, at least, was polite. Often he wasn’t and ran into endless trouble with officialdom. But, contrary to expectation, he was a loyal Davis Cup team man and never forgets his friends.

He still plays with a little band he helped create in Douglaston, New York, where he grew up with Irish-American parents and two brothers. Unable to fulfill his ambition of being a rock star, he married one: Patty Smythe.

Weeks at No. 1: 170 ... Consecutive weeks at No. 1: 58 ... Year-end No. 1: 4 times

Photo by Allsport/UK

Bjorn Borg

There was no question that six triumphs at Roland Garros in eight politically interrupted years when the cool Swede opted to play for the banned World Team Tennis league in America established Borg as the pre-eminent clay court player of his era — probably of all time until the arrival of Rafa Nadal. But where does he stand when it comes to grass? Five straight Wimbledon titles from 1976-80 lift him high up that scale, and it was this extraordinary run of success on a surface not naturally suited to his game that turned him into world star.

Timing, however, is everything and, with John Newcombe fading, Borg simply made the most of the absence of a great serve-and-volleyer until the arrival of John McEnroe. Nevertheless, the quietly spoken and flawlessly behaved Swede showed what could be achieved by mixing backcourt tennis with judicious net play and some of his matches — notably the classic five-set Wimbledon semi-final against his great friend Vitas Gerulaitis in 1977 — remain indelibly in the memory.

In a different era, Borg took care of his lithe body but not to the extent of missing out on the nightlife European cities had to offer and it was in discotheques in Paris, London and Rome that one saw a different Borg. After a glass of wine or two, he was ready to admit that his image of the unblemished sportsman was enhanced by the fact that his halo shone brightest when compared to his three rabble-rousing rivals, Ilie Nastase, Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe. The latter, in particular, became a good friend.

Borg’s early retirement at the age of 26 — after 66 tour-level singles titles — came about when the ITF refused to grant him a reduction in the number of required tournaments he had to play. “I have been playing tennis non-stop for 10 years and if you don’t reduce my schedule, I shall quit,” he threatened. They didn’t and he did. Champions of Borg’s caliber can be very stubborn.

Weeks at No. 1: 109 ... Consecutive weeks at No. 1: 46 ... Year-end No. 1: 2 times

Photo by Matthew Stockman/Getty Images

Andre Agassi

Soon after he surprised the tennis world by marrying Steffi Graf in 2001, I asked Agassi while he was playing the Paris Indoors at Bercy if he recognised the young rebel he used to be. He smiled. “No, who was he?” There had, indeed, been a transformation in how this son of an Iranian-born boxer, brought up in Las Vegas, conducted himself on the ATP Tour.

In his revealing autobiography, Agassi has admitted that he came to view a tennis court as a cage due to the strict training routine his father demanded of him and, in his view, it got little better at Nick Bollettieri’s Academy. But as he started winning big titles, most notably Wimbledon in 1992 after losing in consecutive Roland Garros finals, Andre matured and married the actress Brooke Shields — whose grandfather, Frank Shields, had been a Wimbledon finalist and sporting heartthrob of the early 1930s.

Although the marriage did not last, Brooke, a fluent French speaker, introduced him to more sophisticated European living and helped knock the rough edges off Andre’s personality. His exceptional ball striking smoothed out, too, and his punishing backcourt game soon made him one of the most effective champions on the Tour.

Following his Wimbledon win by beating Michael Stich to take the US Open title in 1994, Agassi went on to collect eight Grand Slam titles to go alongside seven losing finals and an impressive total of 870 career wins and 60 tour-level titles.

Throughout his career, Agassi found himself battling Pete Sampras as his main rival. Between 1989 and 2002 they met 34 times, with Sampras winning 20 to Agassi’s 14. In the 2001 US Open quarter-finals, Sampras won 6-7(7), 7-6(2), 7-6(2), 7-6(5), with neither man breaking the other’s serve — which was remarkable as Agassi possessed one of the game’s greatest returns.

After marrying Graf, Agassi turned his attention to the work he will be best remembered for in Nevada — the creation of Andre Agassi Prep, a school deliberately set in one of the poorest neighborhoods of Las Vegas. The six-foot photos of Churchill, Mohammed Ali, Mother Theresa and Mandela that adorn the walls are Agassi’s message to his students: Never doubt that you, too, can be one of these people.

Agassi’s mid-career climb from World No. 141 back to No. 1 provides plenty of inspiration of its own, with the American even playing ATP Challenger Tour events as he recovered from personal struggles to regain his status atop the Pepperstone ATP Rankings.

Weeks at No. 1: 101 ... Consecutive weeks at No. 1: 52 ... Year-end No. 1: 1 time

Photo by Stan Honda/AFP via Getty Images

Stefan Edberg

The youngest of the three great Swedes who gave tennis such a Scandinavian flavor in the last three decades of the 20th century, Stefan’s serve-and-volley game was a stylist’s dream: His first serve unfolding like a thrown carpet as, all in one silk-like movement, he advanced to the net to put away one of the game’s great backhand volleys. The fact that he played with a one-handed backhand was wholly due to the technical expertise of an underrated coach, Percy Rosberg, who remained in the background while telling Bjorn Borg to keep his two-hander and telling Edberg to get rid of his. How right can you be?

There was another adjustment Stefan, ultimately a 41-time tour-level singles titlist, required before blossoming into the great champion he became. A chance meeting with the former British Davis Cup player Tony Pickard provided it. Bumptious and opinionated, Pickard offered a total contrast in personality to the shy Swede and promptly set about transforming Edberg’s body language. The slightly stooping, head-rolling gait was not tolerated. “Head up, chin up, get your shoulders back! If you want to be a champion, walk like one!” were Pickard’s instructions and Edberg listened.

A new confidence flooded into his already technically correct game and the breakthrough at the Grand Slam level came when he defeated compatriot Mats Wilander to win the 1985 Australian Open at a Melbourne Park bedecked with blue-and-yellow flags being waved by the thousands of Swedish college students studying in the city. With the next Australian Open being played in January 1987 to effect a date change, the Swedish fans were back to compete with the locals as Pat Cash tried, and failed, to prevent Edberg retaining his crown.

Soon it was clear that Boris Becker, who had won Wimbledon at 18, would become Edberg’s most consistent rival. The Swede won their first duel in a Wimbledon final in 1988, lost to the powerful German in 1989, but beat him when they met for the third straight year in the London title match. If asked today, Edberg will still not have coherent answers to how he lost to the 17-year-old Michael Chang in the Roland Garros final of 1989 — he broke early in the fifth set before losing it 6-2 — but soon it was time to turn his attention to the US Open and once again Pickard played a crucial role.

In eight attempts, Edberg had only managed two semi-finals in a raucous city that grated on his nerves. Pickard finally changed the way Stefan engaged with New York, keeping time spent at Flushing Meadows to a minimum and finding him a quiet hotel out on Long Island. The result was devastating for Jim Courier, who lost the 1991 US Open final to the rampant, well-rested Swede 6-2, 6-4, 6-0.

Finally at ease with his surroundings, Edberg was back the following year to disappoint New York fans once again by defeating Pete Sampras, who had already won the first of his five US Open titles, 6-3, 4-6, 7-6, 6-2. With Anders Jarryd as his partner, Edberg won the Australian Open and US Open doubles titles in 1987 and so achieved the rare feat of being World No. 1 in both singles and doubles.

Weeks at No. 1: 72 ... Consecutive weeks at No. 1: 24 ... Year-end No. 1: 2 times

Photo by AFP via Getty Images

Ilie Nastase

When the first edition of the Pepperstone ATP Rankings were cranked out of a very basic computer at the ATP’s Texas headquarters in 1973, the man at the top of the list was Ilie Nastase. Being the first No. 1 is something that will be his forever. However, the mercurial Romanian — who possessed skills with ball, racquet and movement few others have matched — will be remembered for other things. Frequently letting himself down with furious outbursts that made his fans recoil, “Nasty”, as he was inevitably known, contradicted that side of his character with a funny, generous spirit of which many in need were grateful beneficiaries.

Losing to Jan Kodes in the 1971 Roland Garros final — and to Stan Smith in the Wimbledon final the following year — put him on the world stage and he confirmed his all-surface talent by beating Arthur Ashe to win the 1972 US Open on grass at Forest Hills. Outwitting Nikki Pilic at Roland Garros in 1973 added more stardust to an eye-catching career, but it was in the early years of the ATP Masters Finals that he was most consistently successful.

He won the second ATP Finals ever held, at Stade Coubertin in Paris, added Barcelona the following year despite being woken up at 2:00 a.m. by press and player pranksters to tell him who he would play in the final that day (it was Stan Smith), and then triumphed again at Boston. For reasons no one could work out, Ilie managed to lose on grass at Kooyong to the clay-court expert Guillermo Vilas in 1974 but had his hands on the trophy for the fourth time in Stockholm the next November at the season finale.

That last ATP Finals win was worthy of a movie script. He behaved so badly in the round robin against Arthur Ashe that the ATP president said, “That’s it. I won’t take this anymore,” and left the court, putting himself in the wrong. When referee Horst Klosterkemper tried to explain that to him, Ashe, for one of the very few times in his life, lost his temper. “Don’t tell me the rules,” Ashe yelled. “I wrote them!”

Contrite as ever, Nastase was hiding behind a curtain in the locker room and the next morning at the Grand Hotel, approaching Ashe timidly at breakfast, he went down on one knee and, offering a bunch of flowers, apologised. Both players were re-instated and Nastase beat Bjorn Borg in the final, ultimately closing his career with 64 tour-level singles titles.

Nasty or not, Ilie’s vineyard outside Bucharest now produces 15,000 bottles of a very good vintage every year. It is called… Nasty.

Weeks at No. 1: 40 ... Consecutive weeks at No. 1: 40 ... Year-end No. 1: 1 time

Photo by Patrick Smith/Getty Images

Bob Bryan & Mike Bryan

Mike is the eldest by a minute or two, but it never mattered. Mike and Bob were twinned at birth and marched in tandem through a doubles career that blew up the record books. They were joint World No. 1 for 438 weeks with Mike, by teaming occasionally with other partners, topping that at 506. They were No. 1 for 139 consecutive weeks and became the only team ever to win all four Grand Slam titles in a year twice — a Grand Slam double for masters of the art.

In all they collected 119 titles on the ATP Tour, leaving Mark Woodforde and Todd Woodbridge in second place with 61. In addition, they appeared in 59 other finals. There was an Olympic gold medal in London in 2012 and a Davis Cup record of 25-5.

They looked and behaved like two all-American boys in an understated way, never as outgoing as their father Wayne, a lawyer who was a flamboyant master of ceremonies at various sporting events. But Wayne and their mother Kathy were both good players and, growing up near Oxnard, California, the boys learned well. They travelled well, too, staying in Europe for longer than most Americans on the Tour, flying the flag in a manner most Americans would want it flown, patriotic but polite. So it was not surprising that their first Grand Slam win came at Roland Garros in 2003, the year they won the ATP Finals in Houston.

But the consistency which lasted for so long seemed to arrive when the Australian doubles expert David Macpherson became their coach in 2005. They won the US Open that year and, in 2006, added the Australian Open and Wimbledon. In an unusually long coaching partnership, Macpherson stayed with the brothers for 11 years.

It was only when they picked up their racquets that you could really be sure who was who — Mike the right-hander, Bob the lefty. Both were married with children by the time they retired in 2022, depriving the Tour not just of their expertise but of the chest bump that followed each victory and became their trademark.

Carlos Alcaraz poses with the ATP No. 1 presented by Pepperstone trophy last November in Turin. Photo by Corinne Dubreuil/ATP Tour

Carlos Alcaraz

With a smile almost as big as the huge trophy he was holding, standing on centre court at the venerable Queen’s Club London, it seemed preposterous that rising to World No. 1 at the age of 20 as a result of winning the Cinch Championships was not something new for Carlos Alcaraz. The Spaniard had done it before as the youngest — at 19 years, four months — ever to reach the pinnacle of the Pepperstone ATP Rankings when he won the US Open the previous September, slipping behind Novak Djokovic when injury kept him out of the Australian Open and now re-claiming it.

What was new was the grass beneath his feet. Still a novice on the surface, Alcaraz had not been happy with his form in the early rounds at Queen’s but, like all champions, he got better as straight-sets wins over former Queen’s champion Grigor Dmitrov and Sebastian Korda proved. In the final, the only cloud on his horizon on a day of 30-degrees Celsius temperatures was a thigh muscle that required strapping after he had taken the first set 6-4 off Alex de Minaur.

Alarm bells? Not immediately, because the second set was won with equal ease, earning him his 11th tour-level crown. He followed it up by winning his first Wimbledon title three weeks later, dethroning Novak Djokovic in a five-set final.

But staying free of injury may, in fact, prove to be Alcaraz’s biggest concern in the months ahead. On Tennis Channel in May, Jim Courier was asked what struck him most about this dynamic newcomer. “Apart from being better than Rafa Nadal at the same age?” Courier replied. “What makes him special to me is the smile. It’s there win or lose. It is so obvious that he loves the game and being able to transmit that to his fans is priceless.”

The relaxed attitude to his tennis has been nurtured since the former World No. 1 Juan Carlos Ferrero took charge of his tennis at his academy in Valencia in 2013. Winning the Next Gen ATP Finals in Milan in 2021 set Alcaraz up for his breakthrough year when he became the youngest-ever winner of the ATP Masters 1000s in Miami and Madrid and then went on to become US Open champion by beating Norway’s Casper Ruud in a final that would make the winner World No 1.

It was Carlos, of course, and now one is just left to wonder for how many weeks this extraordinary talent will remain on top of the tennis world.

Weeks at No. 1: 29 (Current No. 1) ... Consecutive weeks at No. 1: 20 ... Year-end No. 1: 1 time

Read Part 1 of the Notable No. 1s series.

View all 28 No. 1s in the 50-year history of the Pepperstone ATP Rankings.